In the mid- to late-1990s, Russian leaders saw Robert Kocharyan, first as leader of Nagorno Karabakh and then president of Armenia, as the main obstacle to a deal that would place the majority Armenian republic inside independent Azerbaijan with a “de-facto independent” status. According to recently declassified State Department documents, then Russian foreign minister Yevgeny Primakov said as much to then deputy secretary of state Strobe Talbott in May 1996.

“I recently wrote to the parties describing my philosophical approach to a settlement,” Primakov told Talbott. “I described this approach as maintaining Azerbaijan and Nagorno Karabakh within one state while providing de facto independence for Nagorno Karabakh.

“Generally, I find the Armenians [government of Levon Ter-Petrosyan – Ed.] to be the most constructive, Nagorno Karabakh [i.e., its “president,” Robert Kocharyan] to be the biggest problem, and [Heydar] Aliyev to fall somewhere between the two.”

Primakov’s approach in 1996 broadly followed the Soviet policy in 1988-91 that offered Nagorno Karabakh more autonomy – such as the status of an autonomous republic – in exchange for the end to the campaign for reunification with Armenia. However, as the violence against Armenians in Azerbaijan expanded and the war began in Nagorno Karabakh itself, that approach was repeatedly rejected by Karabakh Armenians.

In another conversation, Primakov told Secretary of State Madeleine Albright in 1997 that he “grew up in the Caucasus and knew their peoples” and that no agreement would be reached without outside pressure. (Primakov grew up in Tbilisi and studied in Baku.)

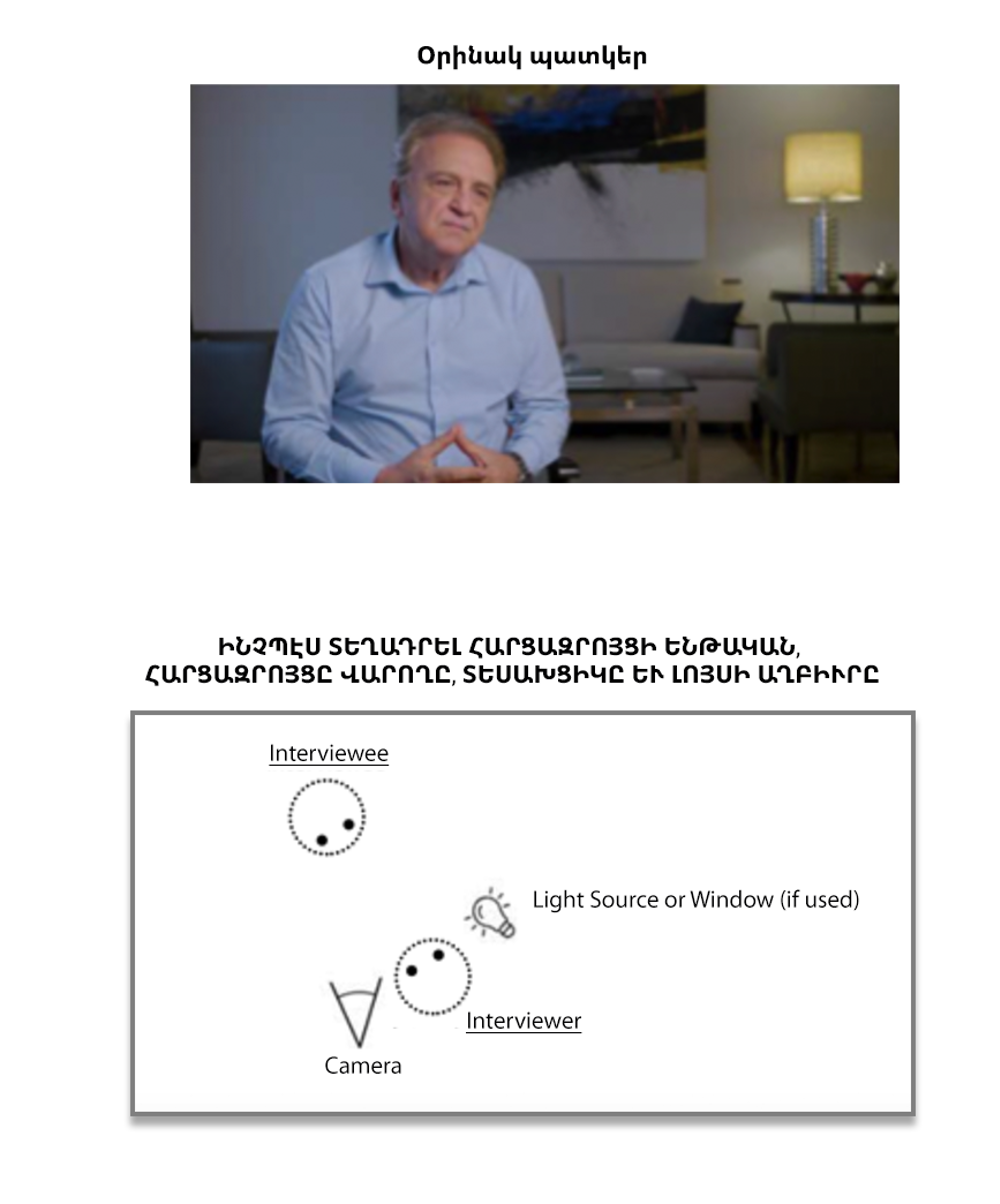

Primakov on Karabakh

In Primakov’s memoirs published in 2016, he recalled his first informal meeting with Kocharyan and then mayor of Stepanakert Maksim Mirzoyan. The two were in Moscow in the spring 1989 for yet another trip to lobby Soviet leaders to consider Karabakh’s transfer to Armenia and Primakov was a senior official with the Soviet Supreme Council (Parliament).

Primakov suggested that Armenians agreed to a higher status – of autonomous republic instead of autonomous oblast – but within Soviet Azerbaijan, something that Azerbaijani leaders at the time were ready to agree to. While Mirzoyan seemed open to the idea, Kocharyan’s response was that the people in Karabakh would not agree to that.

In November 1990, the Soviet government negotiated a “compromise package” between then Armenian and Azerbaijani leaders Levon Ter-Petrosyan and Ayaz Mutalibov that would “restore” the Karabakh autonomy within Azerbaijan and “guarantee” its safety. But neither Ter-Petrosyan, nor Mutalibov were able to win domestic support for the agreement.

A formal agreement between Ter-Petrosyan and Mutalibov was reached with a communique issued in Zheleznovodsk in September 1991, but with the Soviet Union unraveling and war in Karabakh expanding, focus soon shifted to stopping the fighting and reaching a cease-fire.

Kocharyan on relations with Primakov and Yeltsin

In his memoir published last year, Kocharyan described his initially difficult relations with Russian leaders. In May 1996, shortly before his conversation with Talbott, Primakov was in Armenia and Azerbaijan to arrange an exchange of prisoners of war.

Primakov meets with Aliyev. Photo by Eduard Pesov, ITAR-TASS

As part of the exchange, the sides were due to issue a trilateral declaration, mirroring the 1994 cease-fire agreement, but Azerbaijan refused to co-sign a document with Nagorno Karabakh and insisted on a bilateral declaration. Primakov arrived in Stepanakert to try to convince Kocharyan, then NKR’s president, to agree to Aliyev’s demand. Kocharyan refused. Prisoners were eventually released without any declaration issued, but Primakov left upset at Kocharyan.

In February 1998, after Ter-Petrosyan resigned as Armenia’s president over his disagreements on Karabakh policy with Kocharyan and then defense minister Vazgen Sargsyan, Russian president Boris Yeltsin expressed regret over the resignation and apprehension that “tougher” Armenian leaders would come in Ter-Petrosyan’s place.

The following month, Russian leaders backed former Soviet Armenian leader Karen Demirchyan’s bid for the presidency, in opposition to Kocharyan, with Primakov openly endorsing Demirchyan and Kocharyan painted by Russian TV as “pro-Western” and “a radical.”

According to Kocharyan, in their first meeting after his election victory, Yeltsin stared silently at him for a while. “I just stared back,” he recalled in his memoir. Later, Kocharyan tried to convince Yeltsin that he is “neither pro-Western, nor pro-Russian, but a pro-Armenian politician.”

Eventually, Kocharyan developed cordial relations with both Yeltsin and Primakov. By the end of 1998 Primakov shifted his position on Karabakh to the “common state” approach suggested by Armenia and opposed by Aliyev. Kocharyan also built friendly relations with Yeltsin’s successor Vladimir Putin.