#MyArmenianStory – FAQs

(часто задаваемые вопросы)

Что такое #MyArmenianStory?

#MyArmenianStory – это проект Института Арменоведения USC, который собирает биографические истории при помощи платформы краудсорсинга. Цель проекта – записать, собрать вместе и задокументировать индивидуальные события и жизнеописания, из которых соткана история армянского народа. Идея проекта заключается в том, чтобы отыскать и сохранить семейные и другие интересные истории. В качестве интервьюируемого может выступать ваша мама, тетя, сосед или лучший друг – здесь нет никаких ограничений. История каждого актуальна, а вместе они и составляют современную армянскую летопись. #MyArmenianStory – это ресурс, который создаст фактологическую базу армянского опыта, отражающего все разнообразие уникальных людских судеб.

Насколько большим должно быть интервью?

Многие интервью занимают около двух часов, но их можно делать и короче. В нашу коллекцию могут быть приняты интервью любой продолжительности.

Можно ли записывать интервью не на английском?

Да, конечно. Интервью может быть записано на любом языке или даже на нескольких. Главное, чтобы использовался язык, на котором собеседникам комфортнее всего говорить. Во время беседы они могут переходить с одного языка на другой, если им так удобно.

Если интервью проводится не на английском языке, нужно ли мне его переводить?

Необходимости переводить с других языков нет. Интервью на любом языке или комбинации языков будут приняты.

Интервьюер и интервьюируемый обязательно должны быть армянами?

Вовсе нет. Любой человек, у которого есть армянская история, может стать частью проекта #MyArmenianStory.

Интервьюируемый должен быть моим родственником?

Нет, интервью можно проводить с кем угодно. Главное, чтобы человеку было что рассказать, а вам было интересно его выслушать и записать для будущих поколений. Преимущество бесед с близкими людьми заключается в том, что так вы узнаете больше об истории вашей семьи.

Должен ли интервьюируемый быть известным человеком?

Нет, ваш собеседник просто должен быть согласен поделиться своим опытом и сохранить свою историю для проекта. Воспоминания о детстве, о родителях, об эмиграции, создание семьи – все это важная информация, которую стоит записать.

#MyArmenianStory интересен опыт только представителей диаспоры?

Нет. Проект собирает истории всех – и представителей диаспоры, и тех, кто вырос в Советской Армении или современной республике Армения, и тех, кто репатриировал в Армению из других стран.

Что если я захочу взять интервью у человека, а он будет считать, что ему нечего рассказать?

Если ваш интервьюируемый будет смущаться во время беседы, вы можете начать разговор с того, что покажете предмет, который напомнит ему о каком-то моменте его жизни. Это может памятная вещь, передающаяся в семье из поколения в поколение или привезенная из других стран, например, книга, фотография, сувенир, пробуждающий эмоции. Тем самым вы снимете напряжение, способное возникнуть в начале беседы, после чего сможете вернуться к вопросам, которые планировали задать.

Есть ли какие-то возрастные ограничения для интервьюируемых?

Любой человек старше 18 лет может стать героем интервью. Но, конечно, тот, кто прожил долгую жизнь, обладает богатым опытом, наделен хорошей памятью и готов поделиться своими воспоминаниями, был бы оптимальным кандидатом для подобного разговора.

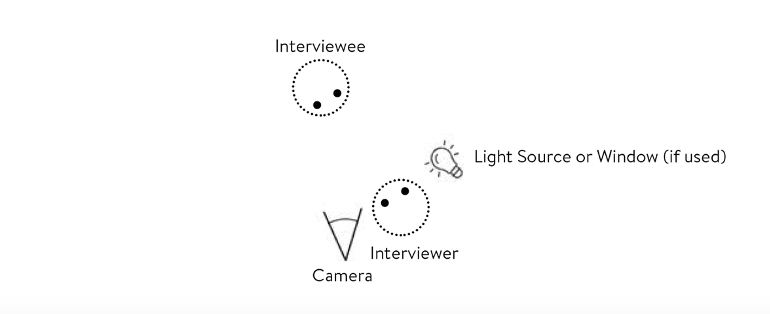

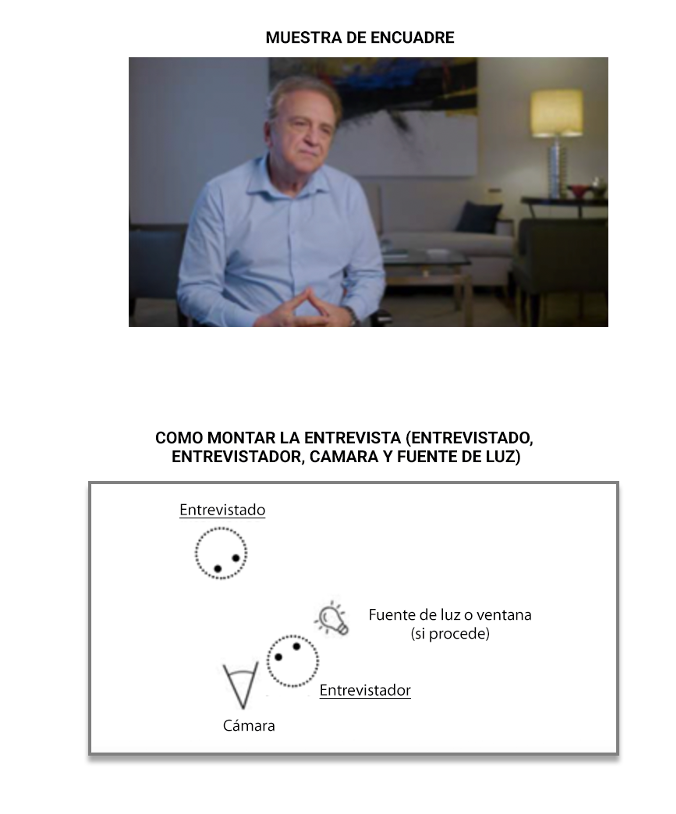

Можно ли проводить интервью удаленно?

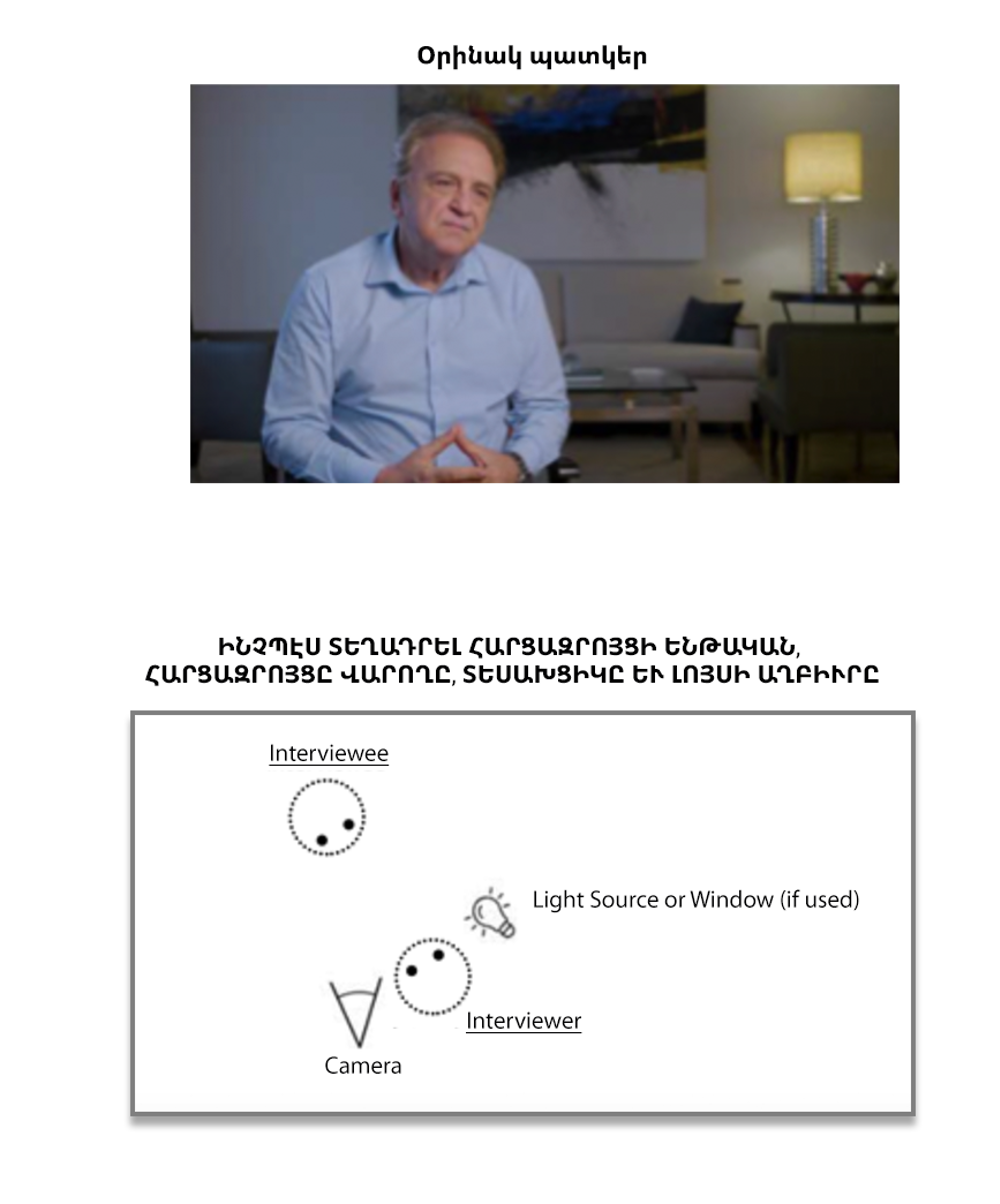

Интервью можно проводить как при личной встрече с собеседником, так и через видео-платформы, такие, как Zoom или Skype. Детальные инструкции по записи интервью можно найти в разделе Рекомендации.

Как загрузить интервью?

На сайте Armenian.usc.edu/myarmenianstory есть раздел Загрузка, через который вы можете загрузить готовое интервью.

В чем разница между коротким и расширенным списками вопросов и тем?

И тот, и другой охватывают одни и те же темы. В расширенном варианте вопросы более детальные и их больше. Вы можете использовать тот список, который вам кажется более удобным или же комбинировать отдельные части каждого из них.

Если я решил использовать расширенный список вопросов, могу ли я пропустить какие-то из них?

Конечно. Вы можете использовать и тот и другой вопросник так, как сочтете нужным.

Можно ли отклоняться от вопросов из рекомендованного списка или задавать не все из них?

Да, во время интервью лучше всего следовать течению беседы и задавать уточняющие вопросы исходя из того, что в данный момент рассказывает собеседник. Если какие-то вопросы из списка окажутся не подходящими для человека, с которым вы проводите интервью, их можно легко пропустить. Также если во время беседы возникают новые темы, которых нет в списке вопросов, вы, конечно, можете о них говорить и задавать уточняющие вопросы не из списка.

Я никогда не брал интервью. Справлюсь ли я?

На самом деле, интервью это просто длинный, более глубокий разговор. Все что нужно для успеха – ваш интерес и согласие респондента. А наши рекомендации и список вопросов и тем, которые могут быть затронуты в беседе, помогут вам в этом.

После того как я загружу интервью, кто будет его правообладателем?

Институт Арменоведения Университета Южной Калифорнии получит права на видео, которое вы загрузите и которое станет частью университетского архива, открытого для исследователей. Но права на запись, которую вы сделали, останутся у вас. Пожалуйста, позаботьтесь о том, чтобы сохранить у себя копию интервью для вашего семейного архива, поскольку если вы впоследствии будете запрашивать копию у менеджеров проекта, на это может уйти много времени.

Что мне делать, если интервью будет прервано?

Заминки часто случаются во время интервью. Если перерыв короткий, просто продолжайте запись интервью. Если же запись была остановлена, продолжайте с новой записи и не забудьте потом пометить все части. С тем, как именно отмечать разные части записи, вы можете ознакомиться в разделе Рекомендации.

Что делать, если собеседник расчувствуется во время интервью или даже расплачется?

Подобное часто случается, когда люди вспоминают важные моменты своей жизни. Дайте собеседнику время на то, чтобы собраться, и затем продолжите разговор. Останавливать запись при этом необязательно.

Что делать, если интервьюируемый предлагает поделиться документами, фотографиями или другими интересными материалами?

Документы, фотографии и прочие исторические материалы очень приветствуются и только добавят интервью ценности, обеспечив его важными визуальными составляющими. Вы можете отсканировать или сфотографировать эти материалы и прислать их на электронную почту Института, либо отправить их оригиналы при помощи предоплаченного сервиса службы доставки FedEx.

Что если интервью было прервано по каким-либо причинам, и у меня нет возможности его завершить? Могу я все равно его загрузить?

Да, можете. В разделе Рекомендации описано, как правильно пометить интервью, состоящее из нескольких записей. Но все-таки, если возможно, постарайтесь завершить интервью.

Может ли кто-то третий участвовать в интервью? Что если другой член семьи прервет беседу или же станет спорить о чем-то из сказанного интервьюируемым?

Было бы лучше, если бы этот член семьи подождал и дал вам отдельное интервью. Брать интервью у двух или более людей сразу, тем более говорящих одновременно, не рекомендуется.

Это может запутать исследователей, которые впоследствии будут его слушать. Договориться о новом интервью с другим членом семьи можно либо остановив для этого запись, либо прямо во время записи.

Как Институт Арменоведения собирается использовать мое интервью?

Институт Арменоведения Университета Южной Калифорнии будет хранить, каталогизировать и создавать цифровые архивы всех интервью, которые впоследствии будут доступны исследователям по запросу.

Где будут храниться все интервью?

В цифровом архиве Института Арменоведения Университета Южной Калифорнии.

Будут ли записи доступны для широкой публики через онлайн-ресурсы? Кто и как сможет увидеть мои интервью?

Записи можно будет получить из электронного архива только по запросу. Открытый доступ к ним через интернет будет недоступен.

Существуют ли какая-то форма согласия на передачу интервью Институту Арменоведения, которую интервьюируемый должен будет подписать?

Интервьюируемый должен дать устное согласие на передачу интервью Институту Арменоведения во время самого интервью. Также интервьюер должен будет подтвердить, что такое согласие было дано в процессе онлайн-загрузки интервью на сайт проекта.

Могу ли я проводить несколько интервью с разными людьми и потом загружать их на сайт?

Да.

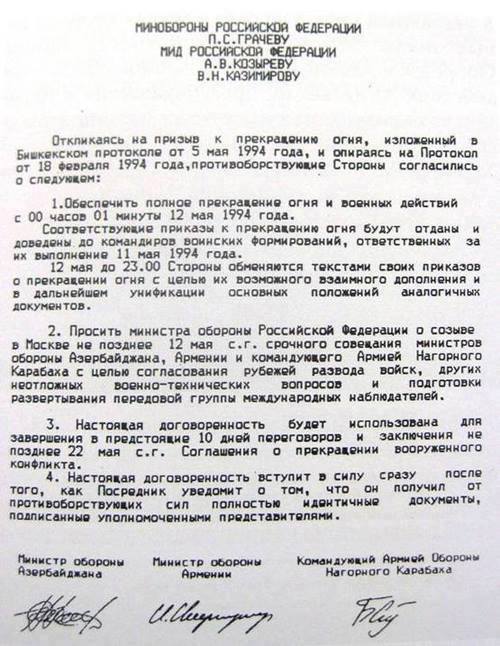

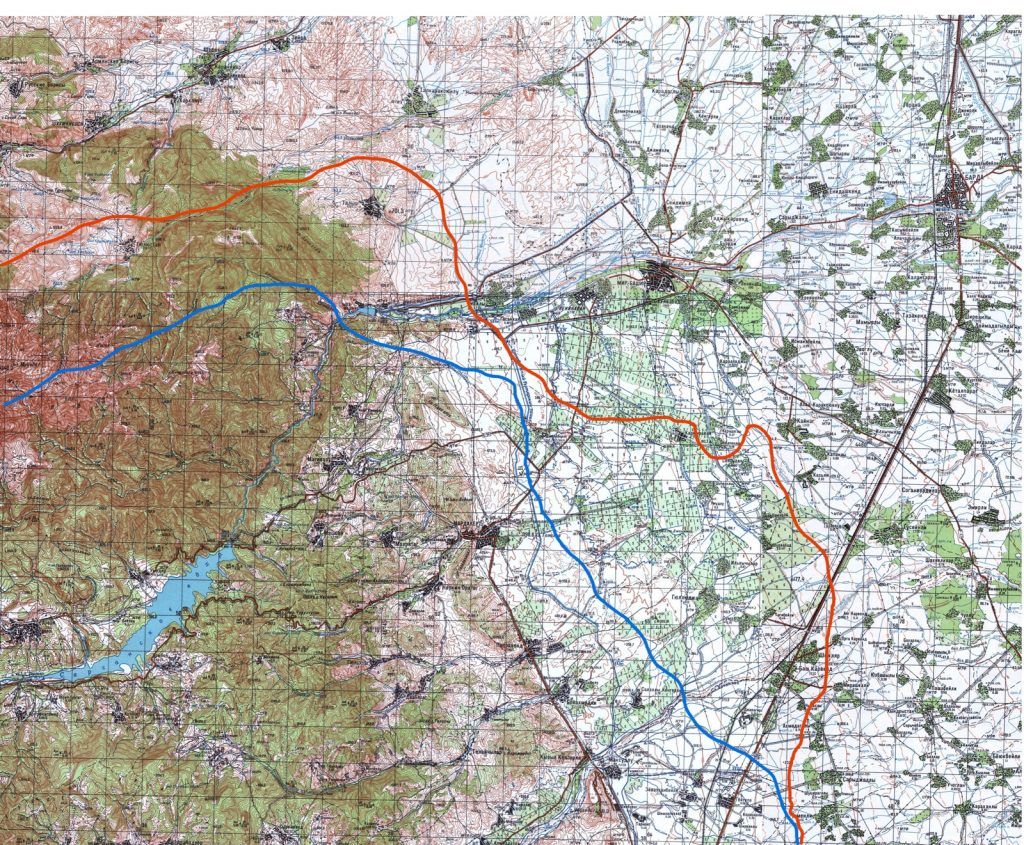

In the meantime, on May 4-5 the parliamentary assembly of the post-Soviet Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) met in the Kyrgyz capital of Bishkek. After debate, the Armenian and Nagorno Karabakh parliament leaders signed the assembly’s protocol calling on the parties to agree to cease-fire. A similar call was made the previous February, during the CIS presidential summit. In Bishkek, the Azerbaijani deputy speaker initially refused to sign. On May 8, Russia’s envoy for the talks Vladimir Kazimirov took the protocol to Baku, where it was signed by Guliyev. Notably, the signing came after Aliyev’s visits to Ankara and Brussels on May 5-7 and the Armenian advance in Karabakh on May 7.

In the meantime, on May 4-5 the parliamentary assembly of the post-Soviet Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) met in the Kyrgyz capital of Bishkek. After debate, the Armenian and Nagorno Karabakh parliament leaders signed the assembly’s protocol calling on the parties to agree to cease-fire. A similar call was made the previous February, during the CIS presidential summit. In Bishkek, the Azerbaijani deputy speaker initially refused to sign. On May 8, Russia’s envoy for the talks Vladimir Kazimirov took the protocol to Baku, where it was signed by Guliyev. Notably, the signing came after Aliyev’s visits to Ankara and Brussels on May 5-7 and the Armenian advance in Karabakh on May 7.