The interview was originally published by CivilNet.

Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov said on April 21 that the parties to the Nagorno Karabakh conflict have been presented with projects that suggest a step-by-step solution of the conflict, which “are currently actively discussed.” Lavrov added that these proposals suggest moving towards a step-by-step settlement, assuming at the first stage the solution of the most pressing problems, including the withdrawal of Armenian troops from “some territories around Nagorno Karabakh” and the unblocking of transport, economic and other communications. Armenian Foreign Minister Zohrab Mnatsakanyan responded immediately that “this kind of approaches had appeared in 2014 and 2016, and are not acceptable for the Armenian parties.” He stressed that for Armenia and Karabakh the paramount issues remain security and the status of Nagorno Karabakh.

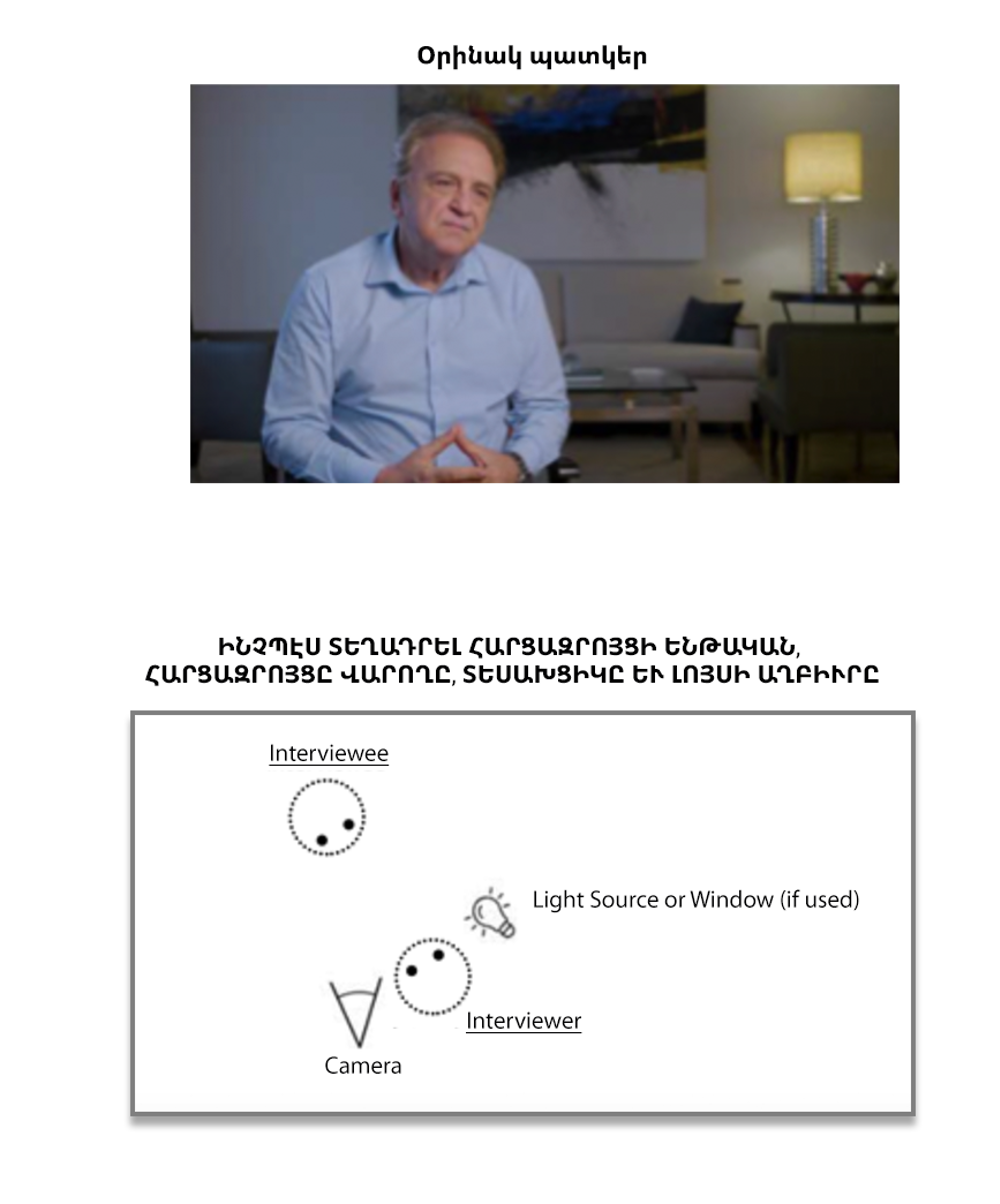

Emil Sanamyan, editor of the USC Institute of Armenian Studies Focus on Karabakh platform and expert on South Caucasus elaborates the recent moves in Nagorno Karabakh negotiations with CivilNet’s Karen Harutyunyan.

– The widely discussed so-called Lavrov plan has been rejected by Armenia before and after the 2016 April war. Meanwhile, Armenia’s Prime Minister and Foreign Minister both have been denying a discussion of any concrete plan in negotiations. What is your view on these statements? – Foreign Minister Lavrov is the most prominent international figure to comment on the Karabakh conflict with some regularity and in the absence of much other commentary at this level, Lavrov’s words always become news. Typically, these comments are prompted by Azerbaijani or Armenian journalists during his media availabilities, and this time was not an exception as Lavrov was answering questions via an online event hosted by Gorchakov Fund.

Lavrov’s previous comments were made six months ago, when he expressed certainty that militarily the situation in Artsakh would remain stable. Those comments must have been based on assurances given by Ilham Aliyev. However, Aliyev has offered that stability as an advance to Nikol Pashinyan, hoping to convert it into serious discussion of Armenian compromises. It appears that Pashinyan has been resisting such discussions. This is the main context for Lavrov’s comments.

– Almost two years have passed since the revolution in Armenia with the new leader Nikol Pashinyan bringing new sort of discourse to the process. For example, he said that any solution to the problem must consider the interests of the peoples of Armenia, Nagorno Karabakh and Azerbaijan, while also stating that “Karabakh is Armenia, period” and that Karabakh’s participation in negotiations is a sine qua non. What kind of impact does this rhetoric have on the negotiation process and atmosphere, if any?

– I don’t think those specific comments have had any effect, as they are vague to the extreme and therefore open to interpretation. Even “Karabakh is Armenia, period” – something that was said by everyone from Leonid Azgaldyan to Serzh Sargsyan before as well – is not a statement of policy, but a very generic slogan akin to “Armenia is Europe, period.”

It is so far unclear if Pashinyan has made it a policy to make Artsakh part of the Republic of Armenia and what intermediate steps he is ready to take in that regard. Until that is clear all we have is “kicking the can down the road” approach that we had before.

– How do you see Russia’s role in the current stage of Karabakh negotiations? Why has Moscow moved to highlight the step-by-step option, knowing well that it puts the Armenian government in an “awkward position”?

– Fundamentally, this has always been the case in the Karabakh conflict and associated negotiations. If we recall the start of this conflict in 1988, the Armenian side was the one challenging the status quo and Moscow was its protector. So, compromise solutions offered by Moscow tended to fall short of the Armenian goal of Artsakh’s reunification with Armenia.

As a reminder: In 1988 Gorbachev’s offer was to raise NK’s status from autonomous oblast to autonomous republic, it was rejected. In 1991 Yeltsin’s offer was to re-establish autonomy and a similar offer was made by Yevgeni Primakov and it was again rejected in the mid-1990s. I would note that all those proposals were so-called “package proposals,” it’s just the Armenian side did not like the content of those packages.

As we know from diplomatic documents, the shift to “step-by-step” option came at the suggestion of the United States in 1997 and at the time it also had Russia’s support. The thought was that if the parties cannot agree on status, why not agree on everything else and keep the status indefinitely unresolved. As we recall, Levon Ter-Petrossian was inclined to agree to that approach and lost his job as a result. 23 years later this remains Aliyev’s preferred option for resolution, and this is occasionally reflected in comments by mediators.

But just as with “package” solutions, judgment on “step-by-step” has to be made on the basis of specific content. In general, the Armenian side is ready for steps that lead to stabilization of cease-fire and normalization of relations. That is the Armenian “step-by-step” approach. But we have yet to see a strong diplomatic effort by Armenia to promote that approach.

– Although there has not been a turn in Armenia’s foreign policy since the revolution, relations between Armenia and Russia have become uneasy in certain spheres. For example, asked about the possibility of decreasing the price of Russian gas for Armenia, Mr. Lavrov stressed that some Russian companies in Armenia are being prosecuted, and “if we talk about being allies, then, perhaps, the alliance should be displayed in all areas.” How would you assess the current state of Armenian-Russian relations? Do Armenia’s domestic developments impact these relations, and to what extent? What implications can these relations have for the Nagorno Karabakh peace negotiations, given Russia’s exclusive role in the region?

– The Russian leadership has been generally unhappy with Armenia events. At the same time, in the absence of obvious signs of change in foreign policy, Vladimir Putin has opted to take a patient approach and basically wait out Nikol Pashinyan. Considering the centralized nature of Russian leadership, personal relations with Putin remain paramount when it comes to relations between countries. The older people get, the harder it is for them to make friends, and it is hard for me to imagine any kind of friendship between Pashinyan and Putin. Armenia-Russia relations will remain in danger of deterioration, be that over Pashinyan’s treatment of Robert Kocharyan or some other issue to which Putin has shown to be sensitive.

Lack of a strong relationship between Moscow and Yerevan is of course a strategic opportunity, which Aliyev will continue to exploit. And I would note that this did not begin under Pashinyan. In fact, the “social distancing” that happened between Putin and Serzh Sargsyan was a key factor that led to the security deterioration in Karabakh and the April War.

– The calamities caused by the COVID-19 pandemic were reflected in the April 21 joint statement of the Armenian and Azerbaijani foreign ministers and the OSCE Minsk Group co-chairs, who stressed the importance of maintaining the ceasefire regime. Will the impending economic recession all over the world and in this region in particular impact the NK peace process in any way?

Uncertainty remains as to how long the current “stoppage” in the global economy will last and if it might be repeated later this year or next. I think it is clear that the demand for oil will remain low for the foreseeable future and Russian and other post-Soviet economies will be struggling as a result. I doubt that the NK peace process, difficult as it is, will become less difficult in these new conditions.

Armenia comes to this crisis better prepared than most other countries because of its natural geographic isolation and existing blockades, and Diaspora networks have helped it adjust to economic disruptions in the past, but Armenia will no doubt be hurting as well. It remains to be seen to what extent Armenia’s leadership will be able to handle this crisis with its challenges and opportunities.