A short novel that shook the Azerbaijani political establishment, when it was published in Russian translation five years ago, is finally out in English. Akram Aylisli’s “Stone Dreams” have been translated by Katherine E. Young and is available via Amazon. Armenian and Italian translations had appeared before.

The author had been condemned in Azerbaijan because the novel is set during the period of anti-Armenian violence in Aylis (Agulis) in Nakhichevan in 1919 and during anti-Armenian pogroms in Baku in 1990. Aylisli said he decided to publish his book after the Azerbaijani government secured the release of axe murderer Ramil Seferov. According to Aylisli, the publication achieved its main goal: “I saved many Armenians from hating my people.”

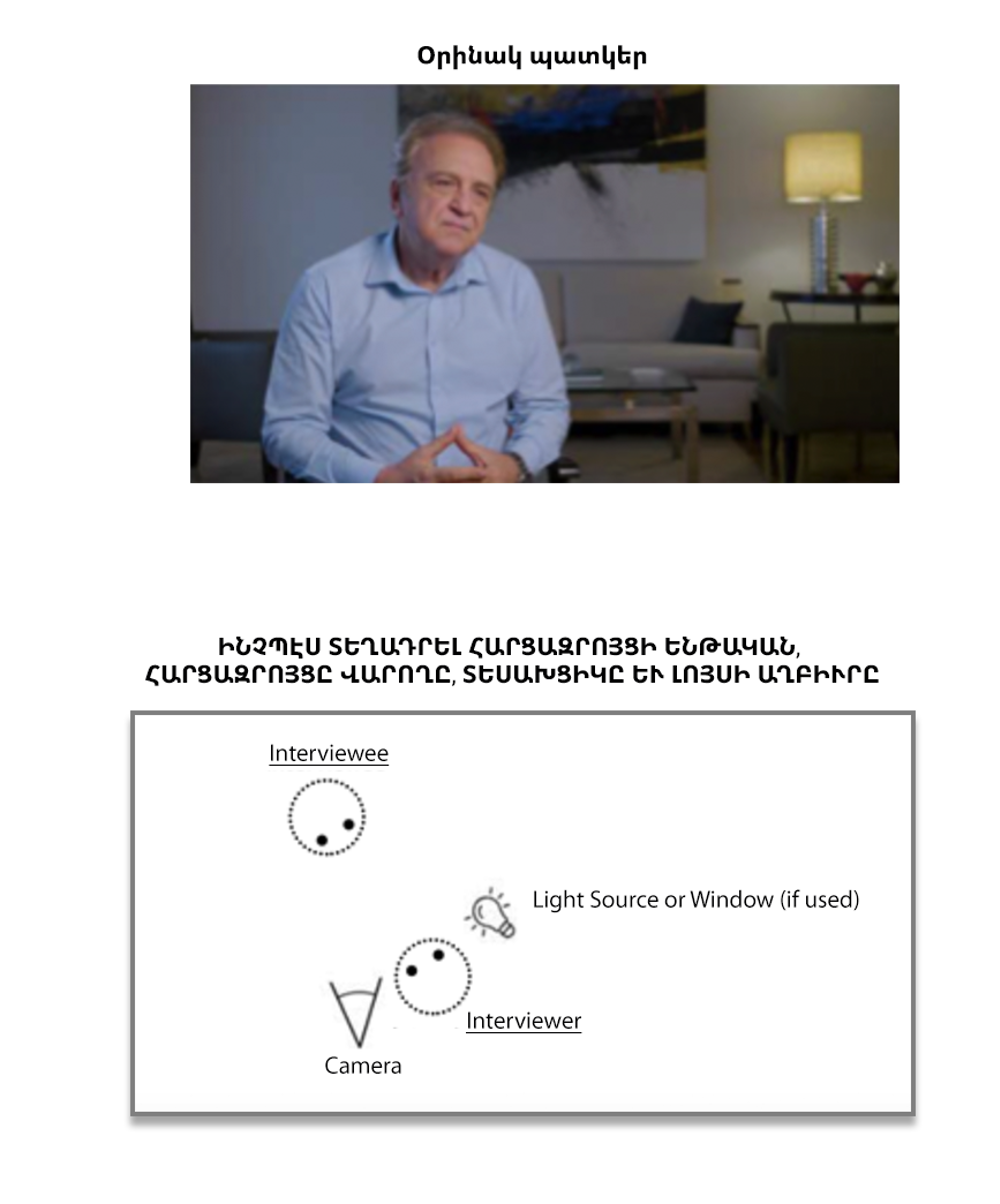

Now 80 years old, Aylisli like many other Azerbaijani dissidents, is prohibited from traveling out of the country. He said in a recent interviewthat he “live(s) completely isolated from society. Completely. It’s as if I’m in exile.”

The book was widely welcomed in Armenia. Below is a review of those reactions, mostly from 2013 and 2014, published by the Caucasus Survey journal, Vol. 2, numbers 1-2, pp. 60-63.

Acknowledgement and praise: Armenian reactions to Akram Aylisli’s novel Stone Dreams

EMIL SANAMYAN

Virgina Tech University;

Predictably, reactions to Akram Aylisli’s novel Stone Dreams were mostly positive both in Armenia and among Armenians in the diaspora. Yet as was the case with many of the novel’s opponents, many of Aylisli’s Armenian sympathizers had not actually read Stone Dreams. They were nevertheless impressed that an Azerbaijani writer, particularly one of some standing with the Aliyev regime, a former member of parliament and holder of various awards and medals, would take such personal risks in “defence of Armenians.”

The context in which Aylisli’s book appeared is of course what makes this work so remarkable. The list of mutual Armenian-Azerbaijani grievances has continued to grow since the Karabakh war ended more than 20 years ago without a final peace agreement. In addition to the dozens still being killed on the Line of Contact every year, threats of new war and hateful, disrespectful rhetoric and actions on both sides continue to feed the propaganda war. Those on the Armenian side have been particularly aggrieved by the destruction of remaining Armenian cemeteries and other cultural landmarks, including in Baku and in Aylisli’s native Nakhichevan1; the many billions the Aliyev regime has been spending on weapons, driving Armenia into greater dependence on Russia and raising the cost of potential war for both sides; the crackdown on public-level Armenian-Azerbaijani contacts intended to build mutual trust; and perhaps most significantly the official praise of the axe murderer Ramil Safarov freed and promoted by the Azerbaijani government.

Aylisli himself has pointed to the Safarov scandal as an important motivation for him to publish the novel that he had written five years earlier. “I thought I wouldn’t have it published for a while,” Aylisli told journalist Shura Burtin last year (Burtin 2013). “But then I said I have to. Whatever it takes, I must stand against what’s going on.” Aylisli also acknowledged that had it not been for the Azerbaijani government’s harassment, the publication of the novel would probably have passed by unnoticed.

Within weeks of Aylisli’s work garnering publicity, Stone Dreams was translated into Armenian, so far the only known translation other than the Russian one. The Azerbaijani original has not yet been published and a Turkish translation may appear before that eventuality. Publisher Ruben Hovsepyan admitted that he decided to publish the novel even before he had read it, because of its public resonance (epress.am 2013a). Translator Leonid Zilfugaryan praise the work for its “spirit of honesty” and said he stayed close to the original without taking translating liberties. Both Hovsepyan and Zilfugarian are accomplished writers and translators, with their translating credits including Tolstoy, Chekhov and Marquez, and Saroyan and Dovlatov, respectively. Hovsepyan also admitted that the translation was made without Aylisli’s permission, whom they were unable to reach, but added that he was ready to offer compensation if Aylisli demands it. Aylisli confirmed that he was not asked for permission, and that if he had

been asked he would not have agreed. But Aylisli also decided not to protest the translation after the fact, even though he did not know either Hovsepyan or Zilfugaryan. “The only Armenian writers I have known [closely] are Hrant Matevosyan and his translator Anahit Bayandur, who studied with me in Moscow, both of them have passed away,” Aylisli added (Radio Azadlig 2013a).

The Armenian reactions to Aylisli’s novel can be broadly grouped into two categories: propagandistic and genuinely sympathetic. Propagandistic reactions tended to focus not so much on Aylisli or his work, but on the official campaign against him, which served to confirm for their authors yet again the nature of President Ilham Aliyev’s regime in Azerbaijan. For example, Armenian Foreign Minister Edward Nalbandyan complained that, “[h]igher officials of Azerbaijan propagate intolerance, hatred, war and proclaim racist murderers as heroes. And what about supporters of peace and solidarity, [such as] Akram Ailisli…? They threaten to cut off his ear” (Armenpress 2013).

Actions and threats against Aylisli were also cited in press releases of the Armenian American lobby. A statement by Congressman Adam Schiff, who represents the largest Armenian constituency in southern California, found that “[w]ith these disgusting acts, the Azeri state reminded the whole world why the people of Artsakh (Karabakh) must be allowed to determine their own future and cannot be allowed to slip into Aliyev’s clutches, lest the carnage of Sumgait a quarter century ago serve as a foreshadowing of a greater slaughter” (Schiff 2013).

Perhaps the least helpful endorsements of Aylisli’s work came from Levon Melik-Shahnazarian, a native of Azerbaijan and political commentator known for his derogatory public rhetoric towards Azerbaijanis. Melik-Shahnazarian saw the value of the work not in Aylisli’s pro-peace message, which he believes has no chance of taking root in contemporary Azerbaijani society, but in exposing the lies in Azerbaijan’s official rhetoric (Melik-Shahnazarian 2013).

One of the few negative reactions, and probably also the strangest, came from Gevorg Danielyan, formerly Armenia’s Minister of Justice (2007-10) who said that he “cannot understand the excitement caused by Aylisli…Those who have read the book did not understand its true meaning. This is another trick of Azerbaijan’s diplomacy. I do not believe that the writer is really subjected to harassment because traitors are usually axed in Azerbaijan” (A1+ 2013).

Among the genuinely sympathetic responses, Hrant Matevosyan’s son David Matevosyan, also a writer, reacted to the anti-Aylisli campaign early on, demanding that “imperialists” from both Russia and the U.S. intervene to guarantee the safety of his “friend, brother and human being” beyond any ethnic group.2 Matevosyan went on to lambast propagandists and politicians in both countries who stink of “khanates and Stalinism simultaneously” (epress.am 2013b). Incidentally, on 13 February the U.S. State Department did react, expressing concern over Aylisli’s safety and noting that the ear-cutting threat had been rescinded (U.S. Department of State 2013).

Another Armenian writer, Levon Javakhian, called Aylisli a brave writer who needed to be defended and urged the Armenian public discourse on Aylisli not to further endanger him at home. In 2008 Javakhian faced criticism for his work “Kirve” (roughly translated as “Godfather”) that included the sympathetic portrayal of Azerbaijani refugees from Armenia.

Javakhian observed that many Armenian intellectuals, while praising Aylisli, still could not rid themselves of anti-Azerbaijani biases. “For me, there is an Azerbaijan of Ramil Safarov and an Azerbaijan of Akram Aylisli. Aylisli’s novel elevated Azerbaijan, and didn’t let it be stereotyped as a criminal with an axe,” he said. According to Javakhian, Ragip Zarakoglu, a prominent Turkish human rights activist and publisher, proposed to print Javakhian’s and Aylisli’s works together (Radio Azadlig 2013b).

In an online Q & A, the most prominent Baku Armenian and perhaps the most prominent of all Baku natives, former chess champion Garry Kasparov referred to intolerant attitudes in Baku, but avoided commenting about Aylisli directly, perhaps mindful that his comments may not be helpful (Argumenty i fakty 2013). His website nevertheless reprinted an appeal by a prominent Russian writer Boris Akunin in defence of Aylisli (Kasparov.ru 2013).

Finally, the most touching reaction came from Lusik Aguletsi, a Yerevan artist who recognized herself in Aylisli’s portrayal of a young Armenian girl who would spend hours painting a church, while visiting her grandmother in Aylis/Agulis. Aguletsi, then 14, recalled meeting Aylisli, then 25, only once. “He talked to my grandmother in a very cultured and tender way, as if he was her son, and when I asked who it was, she said he was “the best educated youth from our village” (Public Dialogues, 2013).

By publishing the novel in Russian rather than its original Azerbaijani, Aylisli made clear that his intended audience also included those outside of Azerbaijan, particularly Armenians and in his interview with Burtin, Aylisli was positive about the novel’s impact: “After that little story Armenians grew kinder towards us. Of course, among them there are some provocateurs who would prefer that I had been killed and for Azerbaijanis to be painted as wild and uncivilized.

Nevertheless, Armenian intellectuals and lots of common people have become a little softer, freed themselves of anger, took a breath of air…” (Burtin 2013). Indeed, with his brave novel Aylisli has provided those Armenians, who continue to hope and argue for long-term peace with Azerbaijan, with an important point of contrast and inspiration.

Notes

1 For further information see www.djulfa.com and https://www.facebook.com/silencedstones/info

2 For more information on Hrant Matevosyan see http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hrant_Matevosyan

References

A1+, 2013. “Opinion: Traitors are usually axed in Azerbaijan”. 27 February; available at http://en.a1plus.am/37500.html

Argumenty i fakty, 2013. “The great chess player at 50: online with Garry Kasparov”. 21

February; available at www.aif.ru/onlineconf/5966/3

Armenpress, 2013. “Civilizational abyss between Azerbaijan and the international community is

deepening. Edward Nalbandian” 27 February; available at http://armenpress.am/

eng/news/709840

Burtin, Shura, 2013. “The pen and the axe: Why should becoming a nation’s conscience make

you its enemy?” Russkiy Reporter, 12 November; available at http://rusrep.ru/article/

2013/11/10/aylisli/ epress.am, 2013a. “Azerbaijani writer to be translated into Armenian: publisher hasn’t read the

novel.” 13 February; available at www.epress.am/ru/2013/02/13/Азербайджанского-писателя-переводят.html

_____. 2013b. “I am shaking the hand of Akram Aylisli”. 9 February; available at

www.epress.am/ru/2013/02/08/«Жму-руку-Акраму-Айлисли»-Армянский-п.html

Kasparov.ru, 2013. “Pro Azerbaydzhan”. 8 February; available at www.kasparov.ru/

material.php?id=511400C916A98

Melik-Shahnazarian, Levon, 2013. “Why is the Azerbaijani government attacking Akram

Aylisli?. Voskanapat, 1 February.

Public Dialogues, 2013. “Akram Aylisli and Lusik Aguletsi”. 4 April; available at

www.publicdialogues.info/node/523

Radio Azadlig, 2013a. “Akram Aylisli about the Armenian translation of his novel.” 15 April;

available at www.radioazadlyg.org/content/article/24957919.html

_____. 2013b. “An Armenian writer on Aylisli”. 27 February; available at

www.radioazadlyg.org/content/article/24914564.html

Schiff, Adam, B., 2013. “Honouring the victims of Sumgait”. Extensions of remarks, 28

February. Congressional Record, 113th Congress (2013-2014); available at

http://thomas.loc.gov/cgi-bin/query/z?r113%3AE28FE3-0001%3A

U.S. Department of State, 2013. Daily Press Briefing, 13 February. Available at

www.state.gov/r/pa/prs/dpb/2013/02/204564.htm